The German genocide you've never heard of

The 2020 Peace Prize exhibition tells the story of the World Food Programme, and it explores the links between food and war. Peace Prize Exhibition photographer Aïda Muluneh has portrayed ten different historic events where food has played a major role - one of these events is the 1904 Herero genocide in Namibia.

Germany becomes a colonial power

Of the countries in present-day Europe, Germany is a relatively recent addition. The nation was not united until 1871, when an alliance of German states under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck defeated the French in the Franco-Prussian War. Germany was now united under one banner and was eager to claim its seat at the table, alongside the other major European powers. Germany, however, was far behind in the race for overseas colonies, and much of the world was already under European control. Africa, however, was an exception.

Chancellor Otto von Bismarck aggressively pursued a policy of imperialism, both for economic benefits and for national prestige. In 1884, Bismarck invited the European powers to a conference in Berlin, where they proceeded to divide up Africa between them. Germany gained several large territories, among them German South West Africa, in present-day Namibia.

In 1870, only 10% of Africa was under European control. In the time leading up to World War 1, that number would increase to 90%.

A battle for power and for food

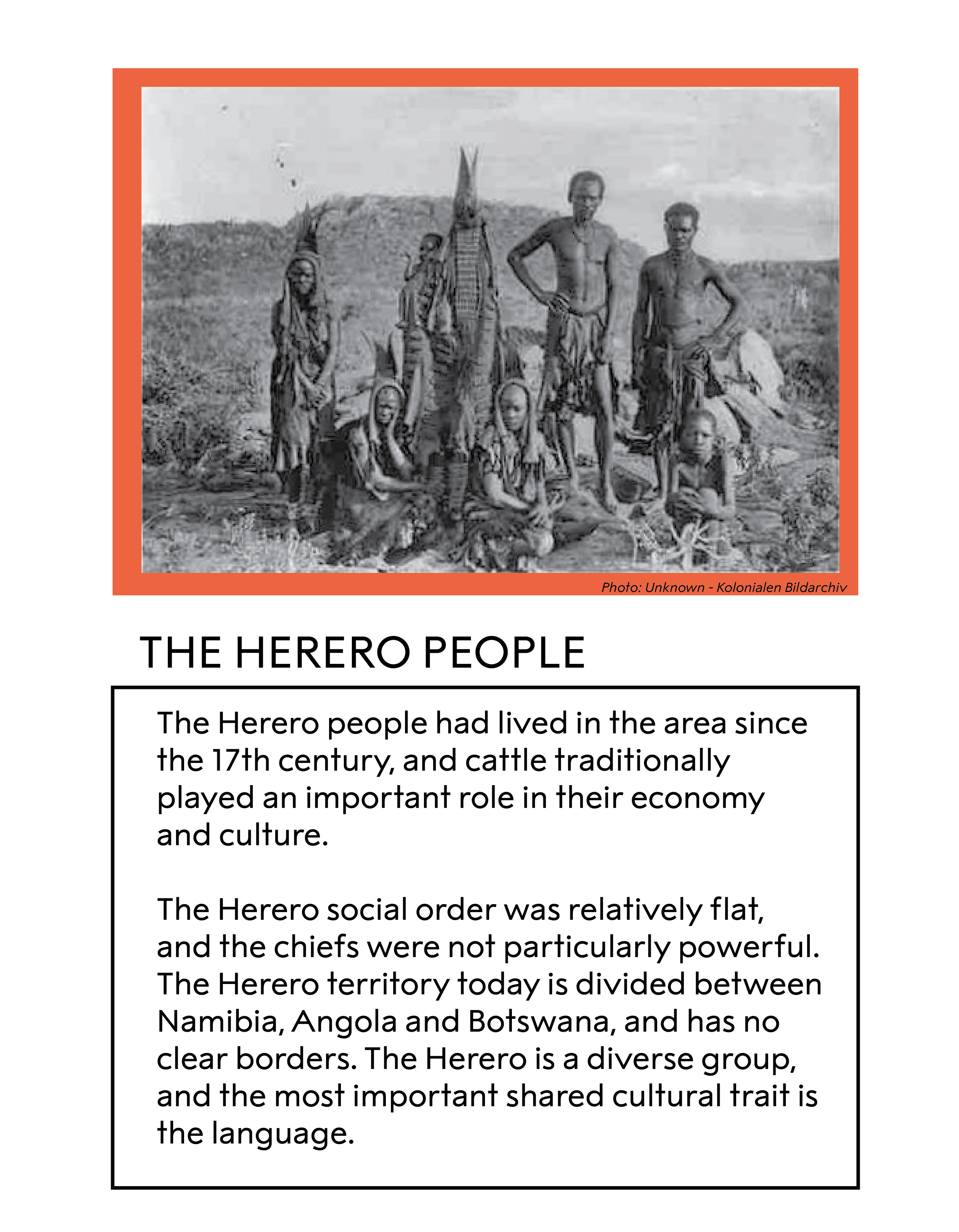

In their encounter with the Herero people, the Germans allied with Herero leader Samuel Maherero. Maherero was a Christian, and this common reference point was a useful basis for cooperation.

After some time, many Germans had settled in the area, and began to confiscate land, steal cattle, and other goods that were essential to the local food systems. The relationship between the Germans and the Herero quickly turned sour. A cattle disease, followed by severe droughts in 1904, became the catalyst for an armed rebellion against the German colonial power. German forces, with modern firearms and racial views that justified their ruthless approach to the rebellion, quickly quelled the uprising. But the Germans did not stop at that.

From power struggle to extermination

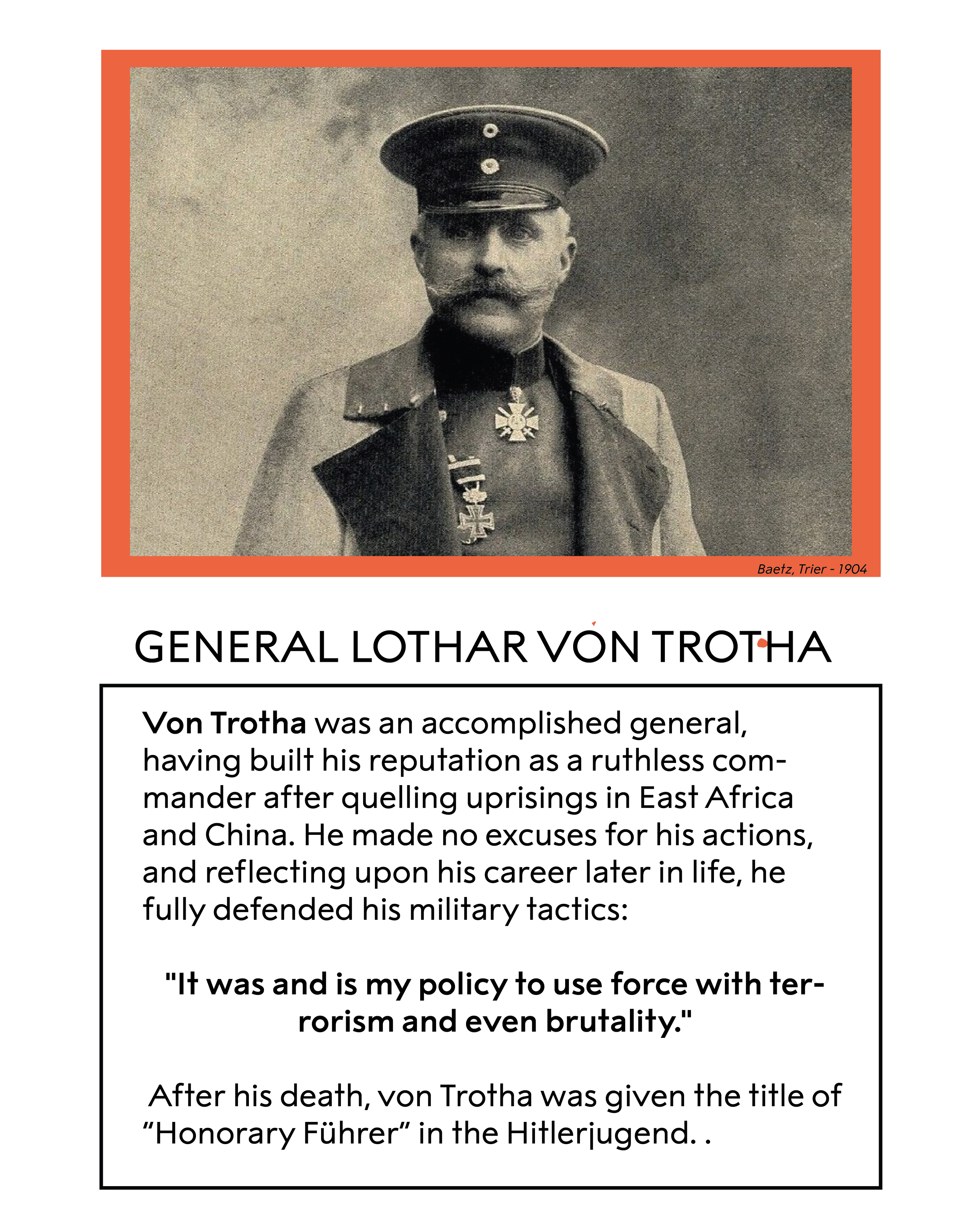

"Any Herero in the German areas, with or without weapons, with or without cattle, will from now on be shot. I will no longer show mercy on women and children. I will drive them back to their people or I will let them be shot at. This is my message to the Herero people. "

After crushing the uprising, the German campaign began to change. What had begun as a military operation to subdue an armed struggle became a general war against the Herero, with the stated goal of extermination. The order came from the very top. On October 2, 1904, General Lothar von Trotha, the supreme commander of the German forces in the country, issued his “extermination order”, which in many ways speaks for itself.

Von Trotha further pointed out that women and children should not actually be shot – only fired toward in order to scare them. The German view was that by avoiding atrocities against women and children, the soldiers would “maintain their good reputation”

The Hereros, meanwhile, mostly attacked German soldiers and military installations, and left German civilians alone.

The marching orders were clear: The Hereros were to be driven out of their lands. To ensure their extermination, water holes would be occupied or poisoned, and any Herero near them would be shot. Thousands of Hereros were driven out into the scorching Kalahari Desert, and without access to water or food, the population succumbed to starvation and thirst. The survivors were put to work in prison camps, and many were subjected to experiments and race research.

A new term was born in the German language: Konzentrationslager – concentration camp.

Approximately 60 000 of 80 000 Hereros were killed between 1904 and 1908, in what is considered the first genocide of the 20th century. After the atrocity was completed, the German occupiers strengthen race laws and escalated the theft of land. Namibia eventually gained its full independence in 1990 – that time, from South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Germany's Federal Minister for Foreign Affairs, Heiko Maas, apologized and recognized the genocide, more than 100 years after it happened – May 2021.

Related:

Listen to history

In which we remain

With this year’s Peace Prize exhibition, the Nobel Peace Center sought to highlight how food was used as a tool for power in conflict. In which we remain is one of ten photographs that seeks to capture a historical moment where food has been used as a tool for power in conflict.

The Herero genocide and the Holocaust were both annihilation policies that involved establishing concentration camps.

"Judging from the similarities between this genocide and the Holocaust, I realized that this was one of the first modern day genocides," says Aïda Muluneh about her Namibian photo In which we remain. "The background was inspired by a photo I saw of the Namib Desert, which is a place of great beauty, but also the grave of the past."

The exhibition is supported by Yara International (Nobel Peace Prize Celebration Partner 2020), Canon (print partner) and Bergesenstiftelsen.

Share: