Hitler's Hunger Plan

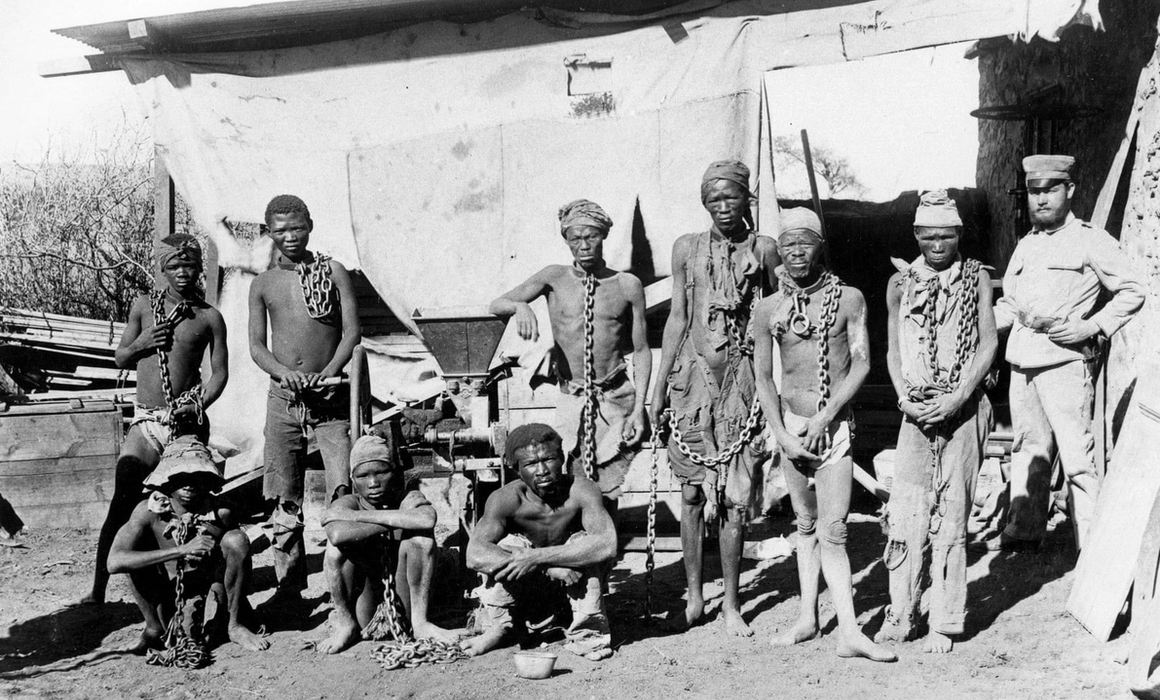

In Hitler’s view, hunger and malnutrition was a key reason behind Germany’s defeat in World War I. For that reason, securing food for his troops became a key priority as he led his nation into the Second World War. A central tenet of Nazi thought was the idea of Lebensraum; the growth and expansion of the German people and its lands. The Germanic race was viewed as superior, and this ideology justified the theft of land and food supplies from those seen as racially inferior, such as Poles, Slavs, and Jews.

As Germany was planning the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, acquiring food for German soldiers was a central to their grand strategy. The minutes from Nazi meetings makes apparent what their expectation for the Soviet invasion was; millions of local civilians would likely die of hunger when German troops confiscated the food supply. This, however, was not seen as a problem. A month later, tanks rolled into Soviet territory, and proceeded with what became known as Der Hungerplan. Approximately 7 million Soviet civilians, Jews and gentiles alike, died as a consequence of Der Hungerplan.

"That we sentence 1.2 million Jews to die of hunger should be noted only marginally."

A HUNGER PLAN FOR THE CAMPS

Forced, deliberate starvation also played a role in the Holocaust. In the Jewish ghettos, the access to food was tightly controlled. It was up to the Nazis to decide who would have access to meat or bread, and the Jewish shops had a very small selection of foods. “It is hard to say how many Jews died from hunger”, says Anette Homlong Storeide, researcher at the Falstad Centre, a museum, memorial and human rights centre in Norway. “Many of those who died in the gas chambers or during transport to the concentration camps, were already emaciated.”

SS and the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) had adopted a general food plan for the camps. The prisoners were to be fed three times a day. The first was a type of coffee replacement, with no sugar. The second meal was to consist of a litre of soup with root vegetables and grains. And for the last meal of the day, the prisoners were to be served 300 grams of dark bread with either sausage, margarine, some cheese, or a spoonful of jam.

Storeide has never come across stories of prisoners who were actually fed these prescribed meals, apart from the occasional ration of margarine. In the last year of the war, the bread ration was down to 50 grams per day.

“This meal plan probably never materialized, and should rather be viewed as a sort of “advertisement”, meant to hide how bad the conditions in the camps actually were. In general, the prisoners were barely fed any proteins or fats. This was seen as important foodstuffs, reserved for the German population.”, explains Storeide.

The combination of poor food and hard physical labour led to emaciation. Many fell ill from the starvation. If anyone became too weak to work, they risked being sent to the gas chamber.

"You taste the flavour of cakes, you taste the flavour of meat – you taste the flavour of what you cannot have. Us humans are actually quite vulnerable, dependent as we are on food and drink. A tiny piece of bread in the morning at five o’clock. That’s what we were given, and then the bowl of this black water."

Anette Homlong Storeide wrote her PhD on Norwegian prisoners in Auschwitz, and has researched eyewitness accounts from the camps. “All prisoners in the camps were starving. But the Jews starved the most.” The distribution of the food in the camps shows how profoundly racist this ideology was”, Storeide explains.

“Non-Jewish prisoners were allowed to receive food from the Red Cross, as well as from friends and family – a privilege not afforded to the Jewish inmates. In the Nazi worldview, they were at the bottom of the hierarchy. Jews that starved to death was not seen as a problem. Quite to the contrary – it was welcomed.”

LISTEN ON SPOTIFY

RELATED ARTICLES:

GERMANY IN THE PEACE PRIZE EXHIBITION 2020

When this year’s Peace Prize exhibition was created, we wanted to show how food is being used as a weapon in war and conflict. The renowned Ethiopian photographer Aïda Muluneh was commissioned to create ten works, illustrating ten different countries and conflicts where food has been used as a tool for power. Nazi Germany is one of these examples.

The picture is titled “Dreams to Ashes”, after a phrase in a poem by Jewish Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel. The artist has drawn inspiration from the pictures she saw in the history books when she learned about the Holocaust in school: "I recall the chilling sight of how the cloth hung on the bareboned bodies of those in the concentration camps."

Watch Aïda Muluneh explain more about this photo and the story behind it:

The exhibition is supported by Yara International (Nobel Peace Prize Celebration Partner 2020), Canon (print partner) and Bergesenstiftelsen.

Share: