Can cat cards save the world?

If we are going to tell the story of how we, a small museum in Oslo, ended up sending two thousand postcards with drawings of cats to a prison in Belarus, we have to rewind time back to October 2022.

It had just been announced that the imprisoned human rights defender Ales Bjaljatski from Belarus was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Ales received the award together with two human rights organisations, Memorial and the Center for Civil Liberties (CCL) from Russia and Ukraine respectively.

At the Nobel Peace Center, we were, according to tradition, in the process of creating an exhibition about this year’s peace prize winners. We had ambitions to create an exhibition that would give hope and inspire our visitors to get involved.

TO INSPIRE IN THE DARK

How could we manage to create hope and inspiration when the backdrop was war, gagging of freedom of expression and then a peace prize winner who was imprisoned for standing up for human rights in his country?

With Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine just a few months earlier, it felt more important than ever that we engaged the public in a valuable way.

The idea for the post card campaign came quickly after conversations with human rights experts and representatives from the peace prize winners themselves. Support for political prisoners is an important part of human rights organisations’ work and can be useful in many cases. In Belarus alone, over 1,400 people are imprisoned for their political beliefs. One of these prisoners is the peace prize winner Ales Bjaljatski. Tried, gagged, and imprisoned for standing up to the authorities.

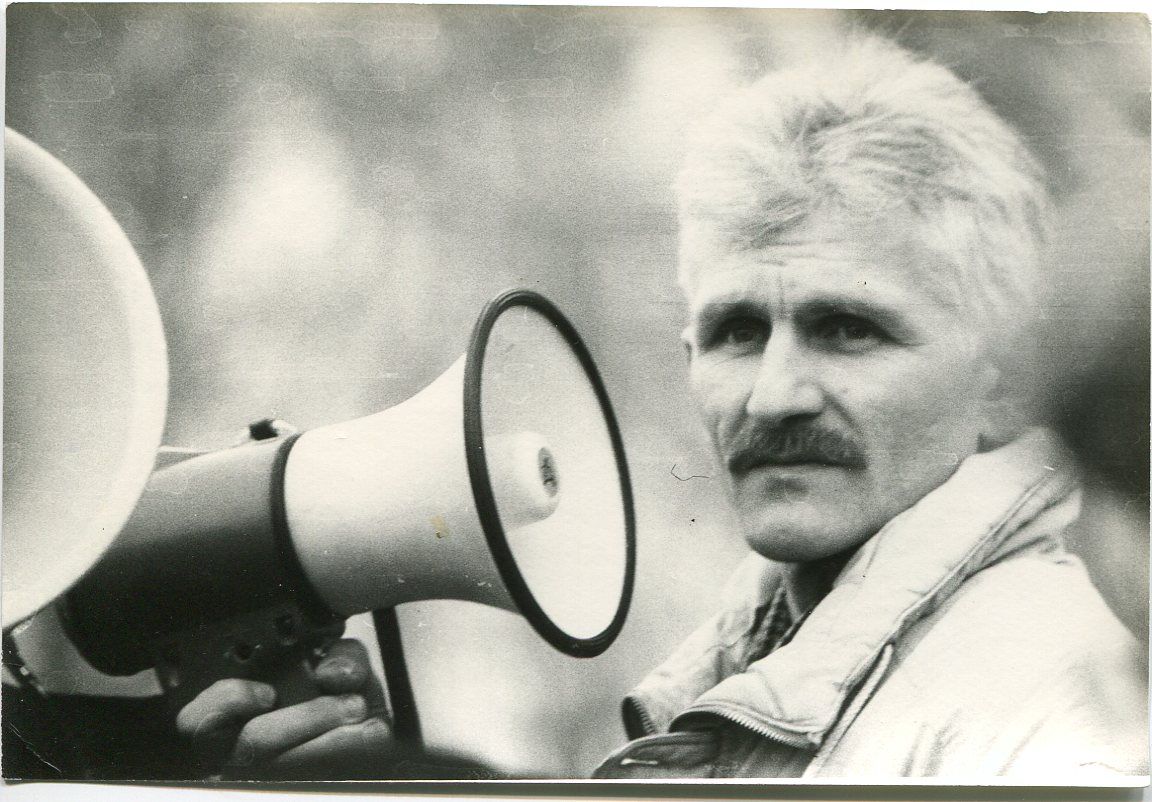

After speaking with Ales’ colleagues and friends, we became quite sure that a campaign where the public could send a greeting to the prison was the right move. We learned that he was imprisoned in a dark, damp, and grey prison cell in Minsk, without law or judgement. One of the things that gave him hope and light in life was receiving letters from the outside. Because the written word has always been important to Ales. He fought for the Belarusian language and had himself been a writer for several literary underground magazines in his youth.

Ales Bjaljatski is a writer and human rights activist from Belarus. He fights for Belarusian language, identity, and culture, and was active in the democracy movement that emerged in Belarus in the 1980’s. He is the founder of the Belarusian human rights organisation Vjasna. Today he is imprisoned for the second time, and is one of the over 1,400 political prisoners in Belarus.

IN THE DARK ALL CATS ARE GREY

The next challenge that presented itself was how we were going to manage to engage the museum audience enough that they would send a postcard to a relatively unknown man, in a country that very few people know anything about?

For us, the answer was that we wanted to make it close, personal and human. We wanted to let the public get to know Ales, as we had over the past few weeks. We wanted to highlight the personal and let the public meet him through photos, video, and a personal letter he had written from prison. We wanted them to know the brave Ales, the man who had sacrificed his whole life and risked everything for his country. At the same time they got to know the human Ales, full of warmth, humanity, who loved his garden, his cat, and his wife.

Even if the theme was heavy, there was still something about Ales that wasn’t. Although the situation he found himself in would seem hopeless to most people, he was full of humour and interest in other people’s daily lives and pursuits.

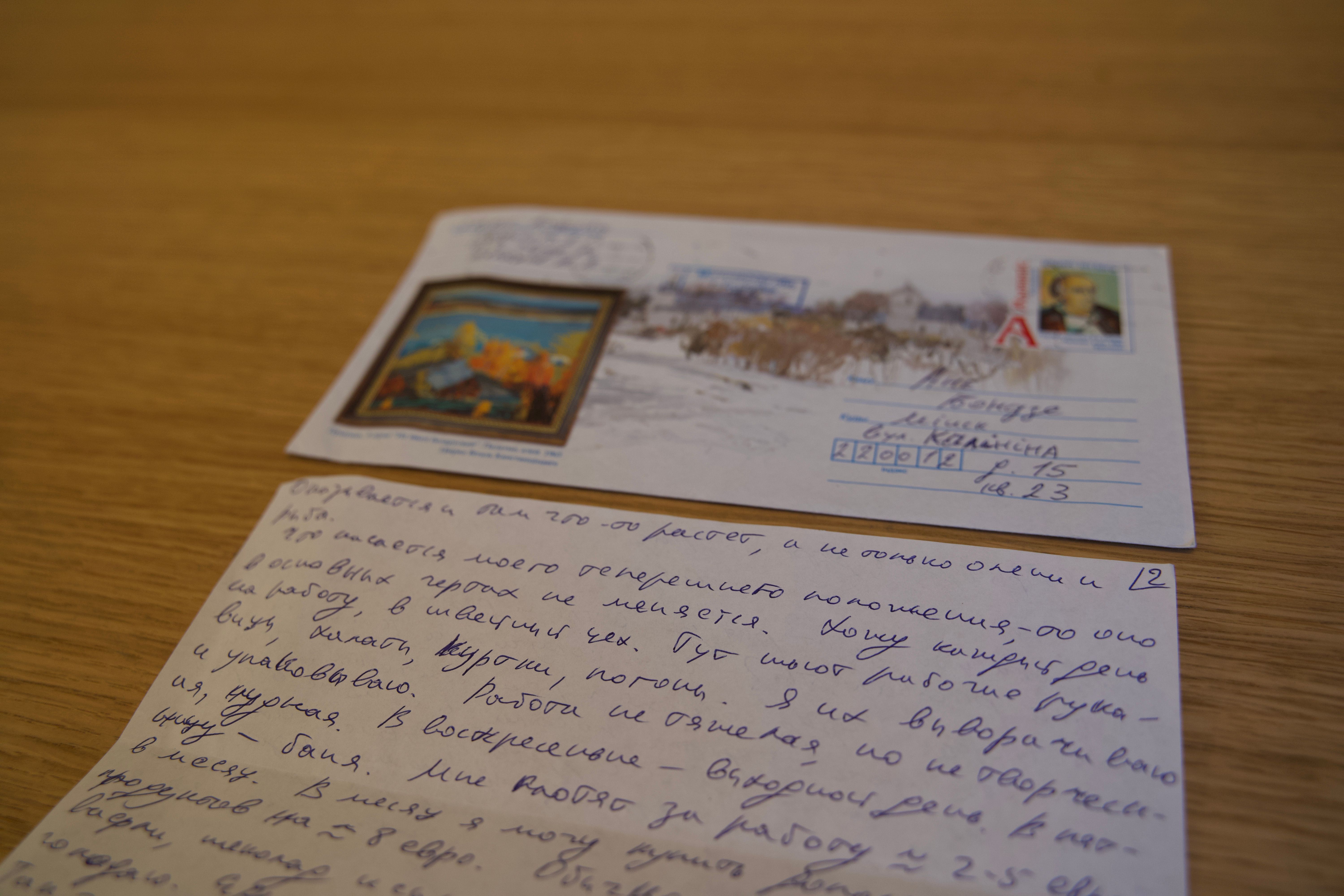

Letter from Ales to Ane Tusvik Bonde. Their families have been pen pals for years.

Recording from the event "hva er greia med Belarus"

THE UNIVERSAL LANGUAGE OF CATS

One of the stories that we could never forget was the importance of letters and cards in adding colour to the (non-metaphorical) grey existence in the Belarusian prisons. Mail filled with drawings, colours, and stickers had served as decorations on the otherwise stripped and sad concrete walls. For many prisoners, these were the only colours they could see while incarcerated.

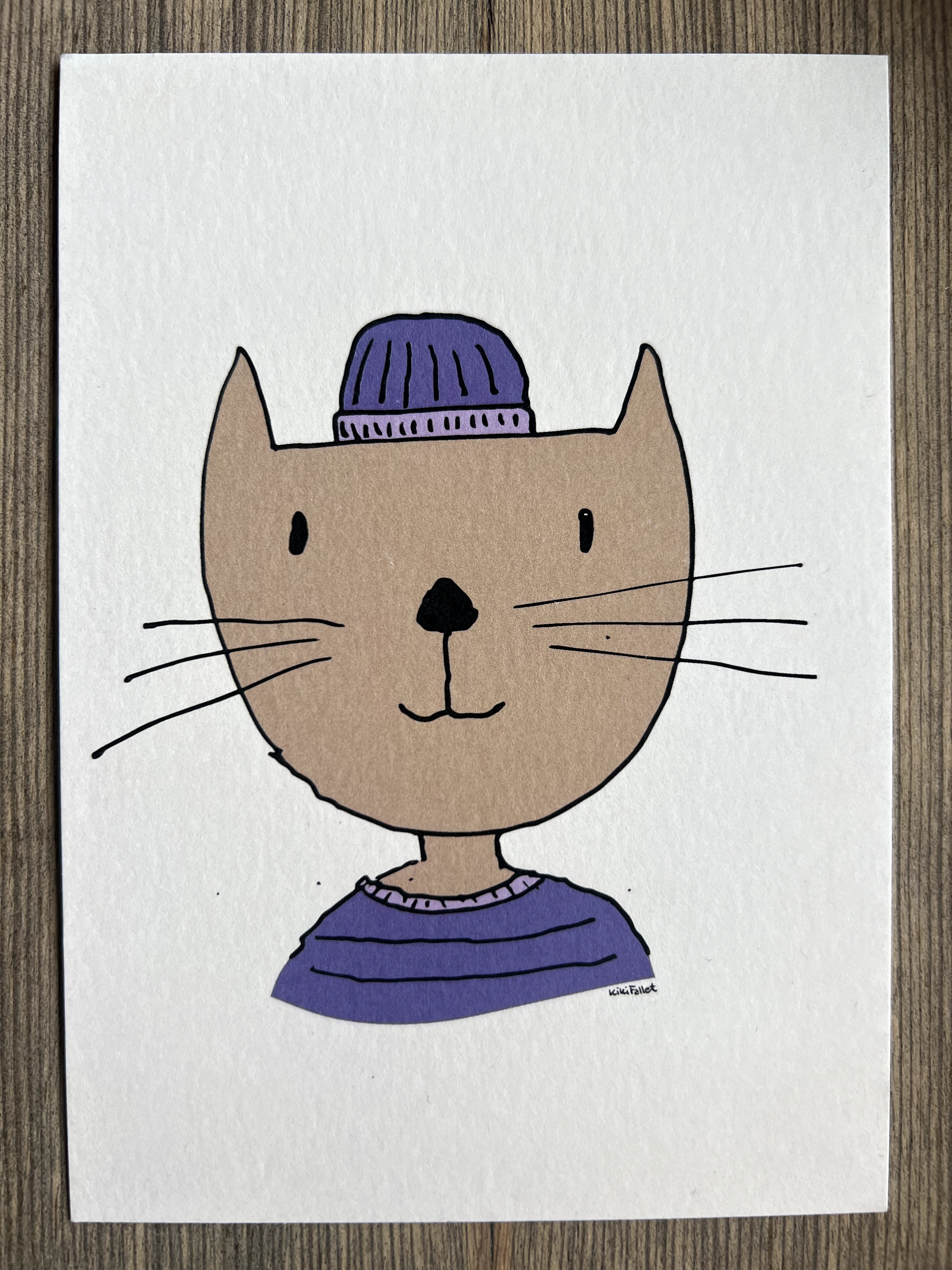

When we had to design the cards, it therefore became important to us that the cards could really help add colour to life. We therefore wanted to decorate the cards with what we knew Ales liked best, namely cats and flowers. We also wanted the cards to reflect something of Ales’ personality to the public. That way, when they wouldchoose which card they wanted to write to Ales, they got to know him a little better. It therefore became important to us that the cards had something of the warmth, hope, humour, and humanity of Ales.

Above all, it was important to show that even though peace prize winners, Belarusians, and political prisoners may seem foreign, they are also people who like completely ordinary things. Something as universal as cats. Who doesn’t like cats?

Since the exhibition was to open just before Christmas, we decided to draw a Christmas motif. We wanted the audience to think about the fact that Ales had to spend Christmas in prison.

Since the exhibition was to open just before Christmas, we decided to draw a Christmas motif. We wanted the audience to think about the fact that Ales had to spend Christmas in prison.

“Grumpy cat” inspired by the cat with the sour face that became an internet phenomenon. We wanted the cat to play on humour, but also show that we were quite upset that Ales is in prison.

Common Flax, or linseed, the national flower of Belarus. The flax flower is an old Belarusian symbol of Belarusian independence. The fax flower is known as a hardy plant, which can manage almost without water or nutrition.

Ales loves cats. Here is a small collage of various cat patterns with a harmonious purple colour that can give colour to his prison cell.

LETTERS AS A FORM OF ACTION

Sending a postcard to a political prisoner may sound both banal and naïve. How much does such a letter really have to say? Does it even have any function or utility?

Letter campaigns are actually one of the most common forms of action for human rights organisations. Amnesty International (which incidentally one the peace prize in 1977) has for a number of years carried out letter and postcard campaigns for political prisoners worldwide.

And it helps. When thousands of letters arrive for a cause, it can be difficult for even the most brutal regimes to ignore. In one out of three cases, the campaigns have actually had an impacton the cases and many have experienced lighter sentences, that the case has been tried again, and in some instances also dismissed.

One should not underestimate how much personal support can mean. Just knowing that you are not forgotten, and that the world out there is thinking of you, that can be a strong motivation. Several of the political prisoners have told of how the letters they received in prison were the only thing that kept them up and gave them motivation not to give up.

The Belarusian human rights organisation Vjasna (which Ales once helped start) told us that they cannot always know whether the letters sent reach the prisoners. Therefore, an important part of such a campaign is to scan the cards, so that you both document what has been written and sent in the event of censorship, but also so that the prisoner can read all the letters when he gets out.

Even if we could not be sure that our cards would reach Ales, they will still help put pressure on the authorities and tell them that the world is watching. In addition, Vjasna was able to tell us that in Belarusian prisons there is a requirement to log and register all incoming mail.

- And we imagined a stern, close-cropped jailer with a grim expression sitting somewhere in Belarus and counting and noting the number of cards with silly cats and purple flowers. 34 cards of cat with hat…54 cards of sour cats…23 purple cornflowers…

THE EXHIBITION OPENS

When we opened the 2022 peace prize exhibition, the cat card campaign had been given a prominent place at the heart of the exhibition. The cards would also get their “fifteen minutes of fame”

During the official opening on 11 December 2022, you could spot peace prize winners, the mayor, the head of the Nobel committee, and a Norwegian influencer writing cards to Ales. In addition, the cards got a few seconds on Dagsrevyen and were talked about on the podcast "Tusvik & Tønne".

Even more important was that after the opening day we could see how our visitors sat down at the table and wrote on the cards. Some of the greetings were funny, some were supportive, some were touching and others were heartbreaking. It was especially touching to see children and young people eagerly drawing their own cats and writing statements of support.

The response was greater than we could have hoped for.

We had managed to engage!

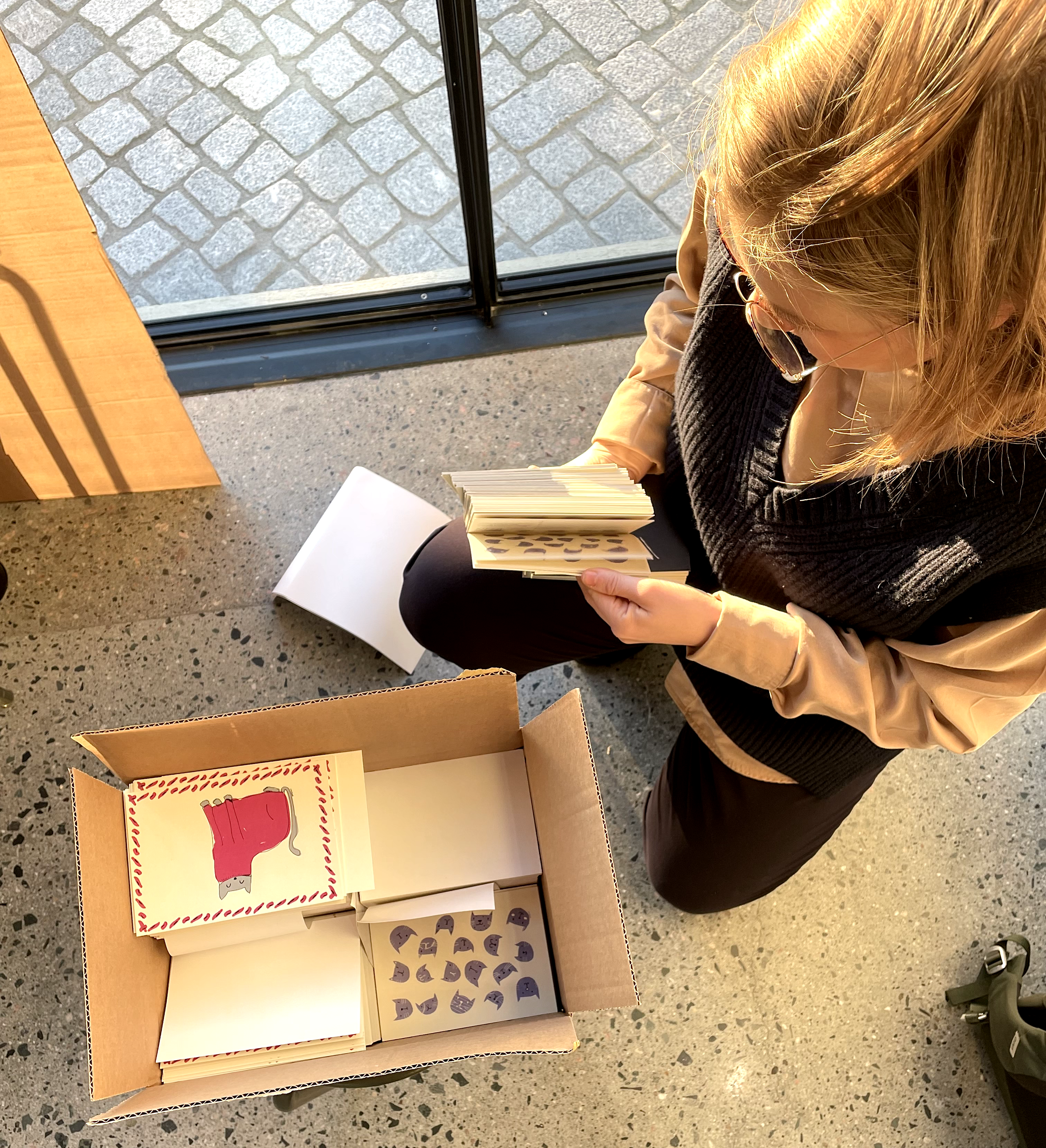

Within a few months, over 2,000 cat cards were written. We packed them in boxes and sent them to Belarus. And hoped that the letters would reach Ales.

Peace Prize laureate Denis Mukwege

Peace Prize laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk

Sigrid Bonde Tusvik and Ane Tusvik Bonde

Berit Reiss-Andresen, leader of the Nobel Comittee

SO, CAN CAT CARDS SAVE THE WORLD?

To answer the question of whether postcards with cats and flowers can save the world: the short answer is no.

Unfortunately, neither the attention surrounding the peace prize in 2022 nor the postcard campaign managed to get Ales out of prison. We’re not even sure if the cards ever showed up.

For Ales, the situation is rather bleak. In March last year, he received a ten-year prison sentence for smuggling and financing “gross violations of public order”. Official statement by the Nobel Comittee.

After the verdict, he was sent to serve time in a penal colony in the city of Horki in eastern Belarus. The prison is notorious for its poor conditions and mistreatment of inmates. The prison authorities deliberately withhold information about Ales, and we do not know much about the conditions he is in. what we do know is that he is regularly placed in penal institutions in the prison, where he is neither allowed to read, write, or have access to fresh air or physical activity.

He has letters and a restraining order, which means that he is not allowed to access a lawyer, or receive phone calls, packages, including those containing vital medicines, or cards with cats on them.

Even if our campaign did not lead to any change in Ales’ prison terms, it does not mean that it wasn’t useful. Although the cat card campaign is over, we will continue to remind the world of Ales Bjaljatski and will encourage the rest of the world to do the same.

What you can do is continue to send letters and cards to Ales in prison. Feel free to decorate them with stickers, drawings of cats, flowers, and things that can add colour to life. Even if they do not reach Ales, they can continue to put pressure on the authorities. We must not let them think he is forgotten.

Updated address for Ales and the other political prisoners from Vjasna can be found on this page.

Share: