A hunger crisis is rarely an accident

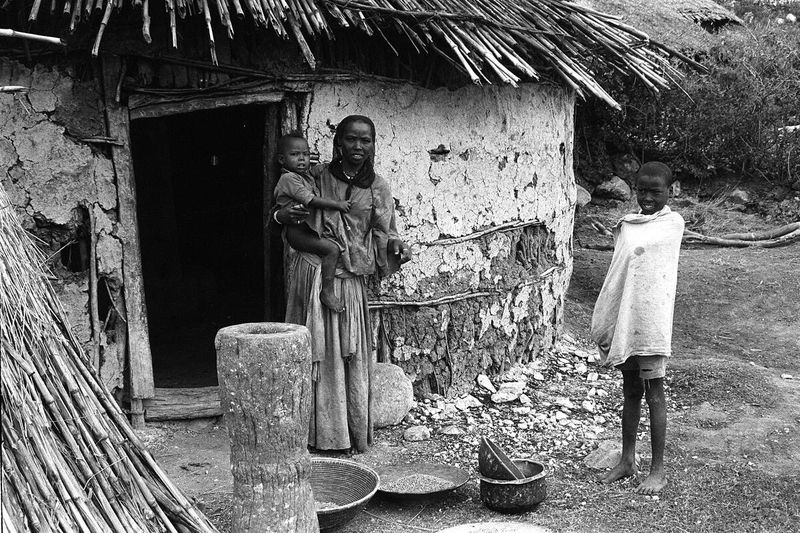

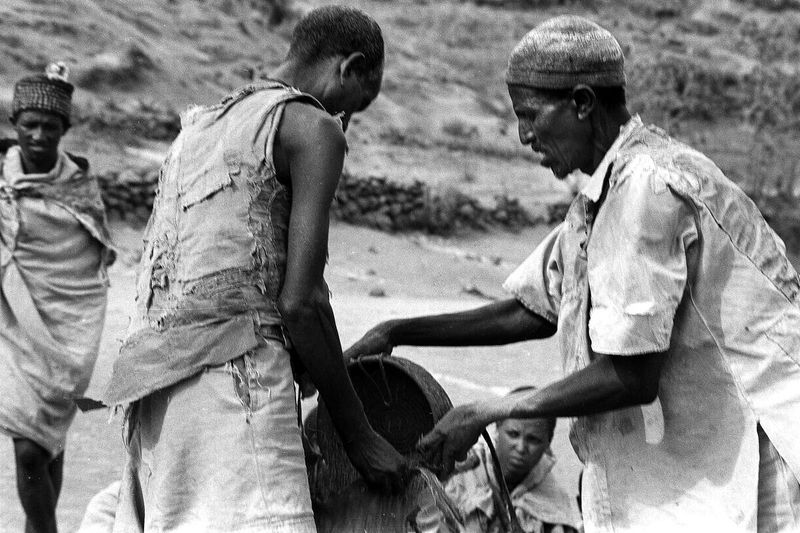

Cycles is the title of one of photographer Aïda Muluneh’s works in this year’s Peace Prize Exhibition. The image reflects Ethiopia’s historical experience with hunger crises. The title points to a pattern that has repeated itself throughout the country’s long history: conflict, hunger, renewal, and hope, before the cycle begins anew. At the same time, agriculture is also a cyclical process, through sowing, growth, and harvest. And sometimes, disruptive droughts and floods rear their heads, these natural disasters humanity still struggles to manage.

History, however, is neither predestined or unchangeable, and a pattern can always be broken, however cyclical it can sometimes seem.

One of the worst hunger crises in modern times took place in Ethiopia in the mid-1980s. As in most hunger crises, the natural causes were only a part of the picture. Most such crises are also political in nature, and may arise or be exacerbated by misrule or deliberate starvation.

At the beginning of the 1980s, Ethiopia was controlled by the Marxist leader Mengistu Hailemariam, who ruled with an iron fist. Regime critics were persecuted, and the top priority for Mengistu and his henchmen was to build a powerful military, to take on rebel groups in the ongoing civil war.

Support for the regime came from the Soviet Union, and another close ally of Mengistu, North Korea’s Kim Il Sung. In many provinces there were, however, armed groups who had taken up arms against Mengistu’s regime.

The resistance to Mengistu’s regime was concentrated in the northern provinces, particularly in Tigray and Wollo. There were many consecutive years of failed harvests in the early 1980’s, and when the rain never came in the summer of 1984, disaster was unavoidable.

Today, many historians claim that the regime deliberately ignored or actively worsened the situation, to weaken these areas’ capacity for resistance. However, the TPLF guerrilla, who fought Mengistu, has also been accused of exploiting the hunger crises to its advantage through this period.

Can a concert save a people?

Mengistu’s regime tried their best to hide the situation form the outside world, but in 1984, a BBC camera crew entered Korem in Tigray. They sent footage back to the British national broadcaster, which were immediately broadcast out to a global audience, were left shocked by the images. It was impossible to ignore the pictures of dying children and mass funerals. One of the emaciated children was named Bergode. Tomm Kristiansen, the Norwegian state broadcaster NRK’s Africa correspondent, covered the famine. Many years later, he managed to find Bergode, and went to see her and her family.

After the broadcast from Tigray jolted awake the conscience of millions, Irish musician Bob Geldof joined forces with many of the large aid organisations with the aim of arranging a concert. In July 1985, the massive global charity concert Live Aid took place. The concert reached over 1.5 billion people, and collected a total of $127 million for famine relief.

The songs that were written for Live Aid, of which “Do They Know It’s Christmas” is best known, have been ridiculed in the years since for their naïve and uninformed lyrics. In the words of Tomm Kristiansen

"The Ethiopians listened but didn’t say anything. “Do they know it’s Christmas…” Didn’t Geldof know that they had celebrated Christmas for 1.700 years in Ethiopia? Further on in the text; “Here, where no rivers run. They only have their bitter tears.” Hadn’t Bob Geldof heard about the Nile? "

No one really knows what happened to the $127 million. Some of it was successfully deployed as emergency aid, while some fell right into the hands of Mengistu, who had contributed to the famine in the first place.

To many in the West, Ethiopia became synonymous with hunger and desolation. But much has happened in Ethiopia since 1985. The country has seen long periods of economic growth and been central to the continental cooperation taking place in the African Union, which is headquartered in Addis Ababa. But the cycles continue.

Among the rebels who fought Mengistu’s regime was a 12-year-old boy who had taken up arms to fight the regime that had caused his people so much pain. He was to continue through the ranks of the Ethiopian military after Mengistu’s regime collapsed alongside the Soviet Union in 1991. The name of the boy was Abiy Ahmed Ali, and in 2018 he would reach the apex of Ethiopia’s political system and become Prime Minister of Ethiopia. The crowning achievement of his rise to power would be the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize, which he received for, among other things, a peace declaration with Ethiopia’s rival and neighbour Eritrea. But the cycles, they have continued.

The image of the visionary peacebuilder quickly fell apart. Today, Abiy Ahmed is himself the one accused of atrocities in northern Ethiopia. A generation after the devastating famine under Mengistu, hunger has returned to Tigray and other provinces. The World Food Programme, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2020, is struggling to navigate in a challenging military landscape, where many transport- and communication links have broken down. The food aid is not reaching its destination, and both the central government and their adversaries have been accused of blocking emergency relief.

In the aftermath of the 1983-1985 famine, the country recovered. Today, Ethiopia has systems in place to detect and mitigate food shortages. Still, another food crisis has now emerged. Two peace prize Laureates - Abiy Ahmed Ali and the World Food Programme - are now important players in a struggle where the fate of the Ethiopian people is on the line.

Listen to history

Ethiopia in the Nobel Peace Prize Exhibition 2020

When we created this year’s Peace Prize exhibition, we wanted to show how food is being used as a weapon in war and conflict. The renowned photo artist Aïda Muluneh was commissioned to create ten works, illustrating ten different countries and conflicts where food has been used as a tool of power. Aïda Muluneh, herself an Ethiopian, named the photo illustrating her homeland "Cycles". In the video below she explains why:

Share: